Learn How to Shoot in Manual Mode Pt.2: Shutter Speed

Welcome to part two of this introduction to manual photography. In the first part we covered the lens, focal length, aperture, depth of field and F-stop. If you’re unfamiliar with any of these I suggest reading part one. Now on to shutter speed!

Your Sensors Gatekeeper

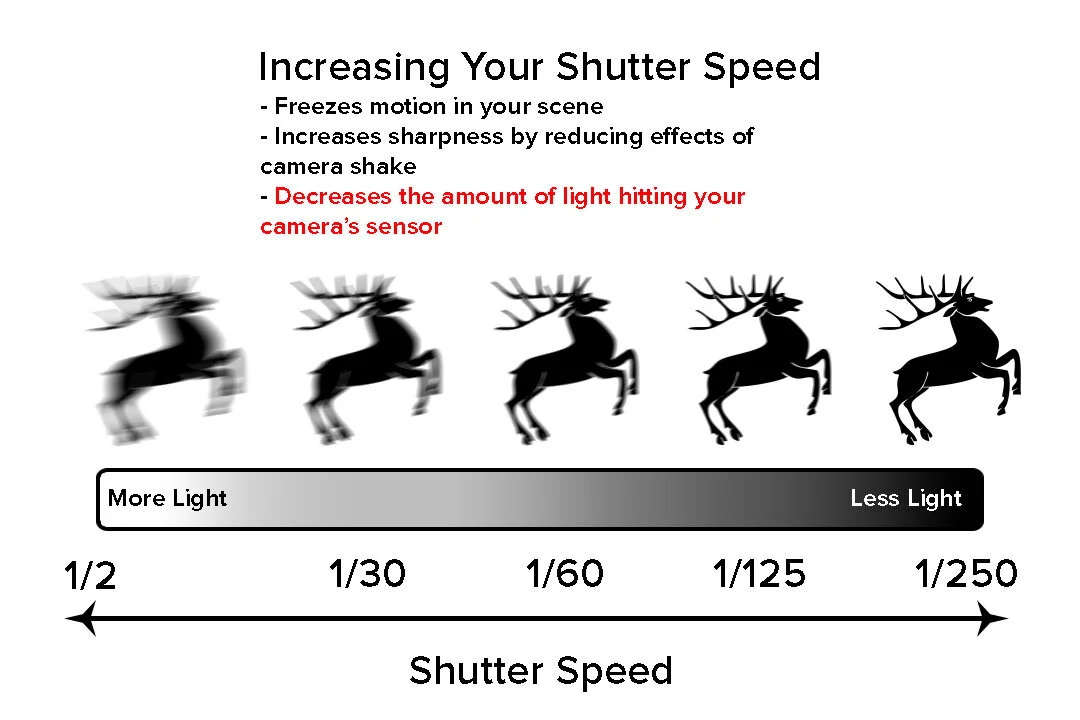

Light is always entering the lens, so the shutter is like the gatekeeper between the lens and sensor. Simply put, the shutter speed is the duration in which your sensor is exposed to light. This speed is incredibly fast and the window for light to pass is only open for a fraction of a second. From this alone we know that a fast shutter speed will have a darker exposure. So if you’re looking to darken your image, increase the shutter speed. If your scene is too dark, then you can lower your shutter. Unfortunately, lower shutter speeds have some caveats but bearing some rules in mind you can work within them.

A Little Light Does A Lot

For speed to exist there must be time. In photography our time base is in fractions of and whole seconds (long exposures). You normally locate your shutter setting next to your aperture setting, (dependent upon camera manufacturer) and you’ll notice you have a wide range of numbers to choose from. The numeric value (X) of your shutter speed is actually 1 divided by X. Meaning a shutter speed of 200, actually means 1/200, so that curtain hiding your shy sensor only exposes it to light for 1/200ths of a second. If your shutter is set to 1000, then the sensor is exposed for 1/1000th of a second.

Careful not to get confused with the numbers that have a single quotation to the right of them, those designate full seconds. For example, a shutter of 20” means that the shutter remains open to incoming light for 20 seconds! These settings are useful for when locked down on a tripod but are useless handheld because the amount of motion blur would make the image unrecognizable. (unless you’re going for something abstract 😉) Which brings me to shutter speeds effect on capturing motion and how to “keep it in check” to maintain image sharpness.

Nutshell: Shutter Speed

High Shutter Speed Value = High Light Situations

Low Shutter Speed Value = Low Light Situations

Increase your shutter speed to freeze speeding objects. e.g. sports, moving cars, wildlife

Safely use lower shutters speeds when stabilized on a tripod whilst shooting scenes with little to no motion. e.g. landscapes, night scenes

You’ll have to sacrifice light when capturing sharp images of fast moving objects. To compensate you’ll have to boost your iso and/or shoot at a lower F-stop. Both of these have there drawbacks. Raising the ISO (sensor sensitivity) too high results in a noisy (or grainy) image, and shallowing your depth of field will make it harder to nail focus. Finding the balance is up to you!

Motion blur is a result of the shutter not being fast enough to keep up with the subject. The light from your scene is changing while the sensor is exposing the single image causing distortions such as “ghosting”, blurriness, light trails, etc.. When shooting handheld, there is also the variable of your hands shaking. Just the slightest shake at too slow of a shutter could ruin your image, appearing soft with ghosted edges.

This can be thought of as a negative, but I think it’s better to look at it as a creative tool. Albeit a limitation in certain lighting conditions, it can be used as a way to give your scene motion, action, feeling, surrealism, etc. It’s up to the artist (you) on how to use this tool to their advantage.

Did you know this photo is actually a streetlight at night shot at a low shutter with camera movements?

Safety Shutter

Handheld situations are what we find ourselves in 90% of the time. You want to snap a sharp and properly exposed picture at a moments notice, right? So what should your safety shutter be? The general rule of thumb is to multiply your focal length by two, then apply that value as your shutter speed. This is the minimum setting in my humble opinion, especially when you get to telephoto focal lengths.

Lenses with image stabilization helps reduce this natural camera shake, which gives you a little more slack on your shutter speed (but hold still!). However, I suggest prioritizing sharpness and sacrificing a stop of light if necessary to maintain crisp focus. Make sure your lens and/or body has image stabilization before you start dropping your shutter below your safety. Some camera systems use lens and in-body image stabilization in tandem to give you very stable shots below your safety shutter speed.

Simply Put..

Safety Shutter Speed = 1/ (Focal Length) x2

You have a 50mm lens, your minimum shutter speed should be 1/100

If your speed isn’t a shutter option on your camera, then simply round up the value to the nearest selectable shutter. It’s always best to round up, you can recover exposure in editing, but you can’t recover sharpness.

Let’s Get RAW

After mentioning recovering exposure in post-editing I feel obliged to talk about the RAW truth. Truth is: RAW is the best quality file that your camera can produce.

RAW format isn’t compressed in camera, it’s strictly sensor data which is then interpreted by your computer. Raising the luminance (recovering exposure) in Lightroom or Photoshop is most easily achievable with a RAW file, simply because the software has exponentially more data to work with. These files have the full latitude of the sensors luminance and color data of the light you captured. The only price you pay is in storage space and post processing time. RAW files aren’t viewable without some brand of Camera RAW software which requires an extra step before exporting to a compressed format (like JPEG) for various social media and web applications.

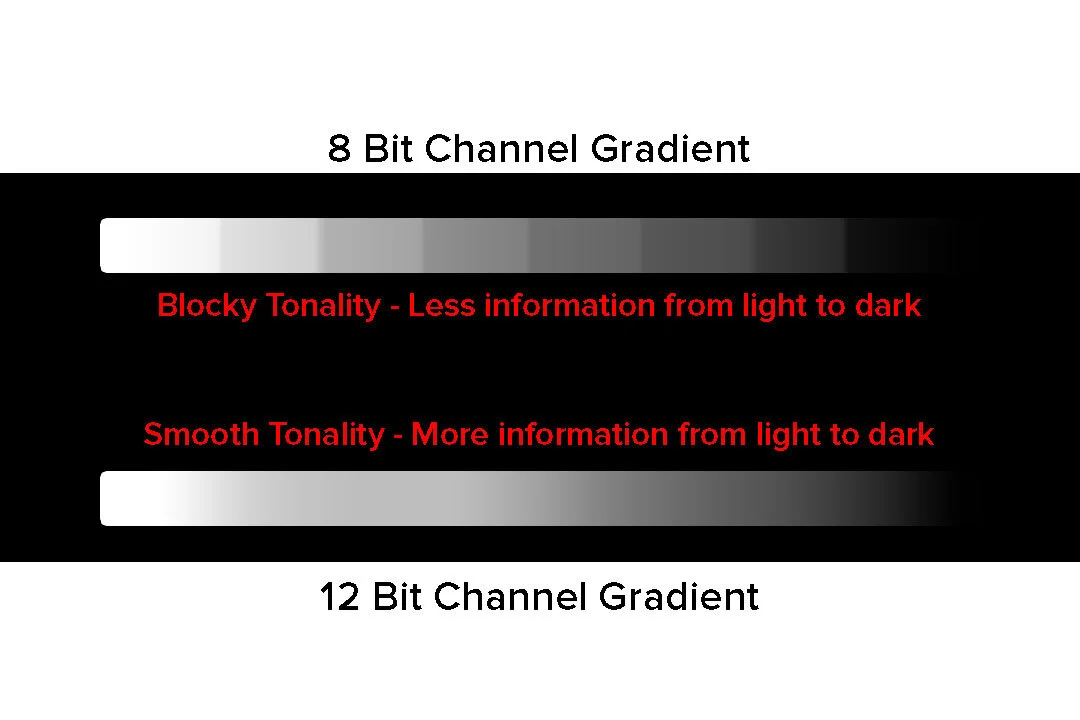

However, if you plan to lightly edit your photos and disk space is a concern then JPEG is still a great option. Practically speaking, if you put a JPEG and a RAW side by side, you wouldn’t see much of, if at all, any difference. Where RAW shines is in its flexibility in post processing. Advantages include having full control of your white balance, working with the full color depth of the sensor (millions of more colors), achieving smoother color gradation and enhancing sharpness. The issue with JPEG is that the camera has already compressed the image in order to save it to such a small file. This means the camera actually throws away parts of your image and duplicates other parts to fill in that space and your color depth is reduced to 8-bits!

Color Depth?

Most modern camera sensors are capable of at least 12-bit per color channel. That means there are 4096 shades of gray (hues) per color channel. You have three color channels: Red, blue and green (RGB). There are 4096 shades of each individual color per channel. So from the darkest red to the brightest red there are 4094 hues of red that can be captured. To get the total amount of colors you multiply all the channels together and that’s how many colors your sensor is capable of producing.

8 Bit Sensor = 256 shades per color channel = 16,777,216 Colors

12 Bit Sensor = 4096 shades per color channel = 68,719,476,736 Colors14 Bit Sensor = 16,384 shades per color channel = 4,398,046,511,104 Colors

Why do you need a trillion colors if it’s imperceptible to the human eye? What’s the point? The point is that you want the highest possible quality at your disposal. Those million shades of “extra” color allow for a smoother representation of reality. More shades of luminance (shades between black and white) mean more retention of shadow and highlight data, as well as smoother light roll off.

When you edit your image, you’ll be happy to have all of that seemingly “extra” data. It’s not extra, it’s just ALL OF IT. JPEG’s throw away color and luminance data, so you’re getting an image that was already edited by the camera itself. You may not be able to perceive every color, but you can tell when a shade of red is inconsistent between brightness values.

BOTTOM LINES:

Faster Shutters Freeze Motion and Enhance Sharpness.

Shoot in RAW & Forget About It.

Now we know about the role of our shutter speed makes in capturing an image, as well as the best format to save our image. There’s one more piece to “The Trinity” and we’ve touched on it briefly throughout the series. It’s the sensor, more specifically the sensitivity of the sensor, which is controlled by the ISO function on your camera. Continue to part three as we go in depth into ISO sensitivity and sensor size.